By Satya S. Chakravorty

January 25, 2010

Source: Wall Street Journal

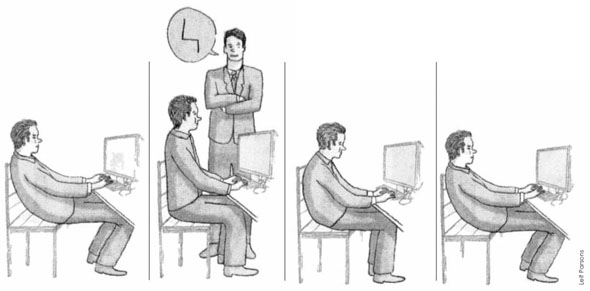

Six Sigma and other programs typically show early progress. And then things return to the way they were.

What do weight-loss plans and process-improvement programs such as Six Sigma and lean manufacturing have in common?

They typically start off well, generating excitement and great progress, but all too often fail to have a lasting impact as participants gradually lose motivation and fall back into old habits.

Questions To Ask Yourself

1. Has your organization achieved lasting gains from process-improvement programs such as Six Sigma?

2. Do you pay much attention to these programs once they move past the initial stage?

3. Are you involved enough in them to judge for yourself whether they are worth continuing?

4. Have you tied employee-performance appraisals to process improvements?

5. Do you plan on keeping a Six Sigma or other improvement expert on your staff long-term?

If you answered no to any of these questions, you should understand how and why so many process-improvement programs fail. Too often, after the project expert moves on to another project and top management turns it focus to another group of workers, implementation starts to wobble. Understanding where the stress and strains are offers managers an opportunity to avoid them.

Many companies have embraced Six Sigma, a quality-control system designed to tackle problems such as production defects, and lean manufacturing, which aims to remove all processes that don’t add value to the final product. But many of those companies have come away less than happy. Recent studies, for example, suggest that nearly 60% of all corporate Six Sigma initiatives fail to yield the desire results.

We studied process-improvement programs at large companies over a five-year period to gain insight into how and why so many of them fail. We found that when confronted with increasing stress over time, these programs react in much the same way a metal spring does when it is pulled with increasing force—that is, they progress though “stretching” and “yielding” phases before failing entirely. In engineering, this is known as the “stress-strain curve,” and the length of each stage varies widely by material.

A closer look at the characteristics of improvement projects at each of the three stages of the stress-strain curve —stretching, yielding and failing—offers lessons for executives seeking to avoid Six Sigma failures. What follows is based on what happened at one aerospace company that implemented more than 100 improvement projects, only to determine less than two years later that more than half had failed to generate lasting gains: